Fable webinar recap

Unlocking the power of accessibility research

How should a UX researcher prepare for research involving people with disabilities who use assistive technology (AT)? How will the session flow? What do you need to keep in mind? Aimed at practitioners new to facilitating accessible UX research, Fable’s recent webinar “Unlocking the power of accessibility research” featured practical advice on how to get started.

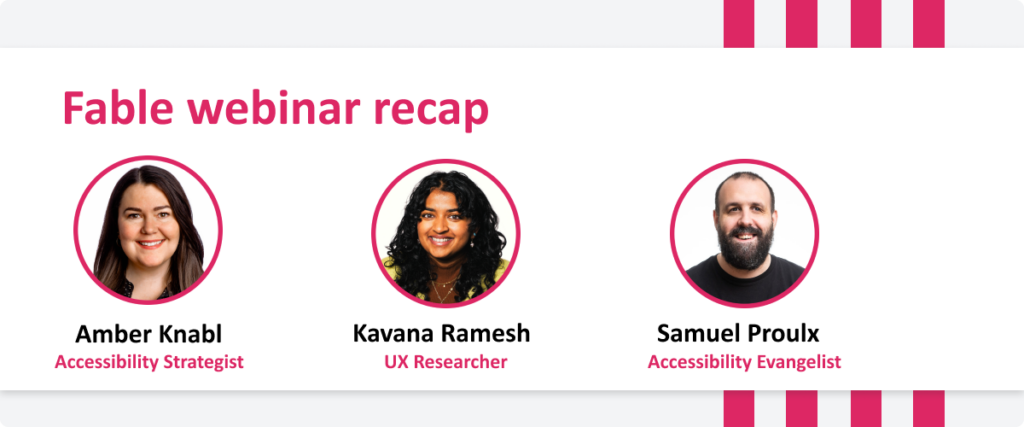

Fable’s UX Researcher Kavana Ramesh and Accessibility Evangelist Samuel Proulx explored examples of accessibility pain points identified in an interview by a user tester, and how a researcher determines their observations and next steps. In a live discussion, Samuel and Kavana reviewed a pre-recorded demonstration they made together that simulates a screen reader participant working with a UX researcher to complete a task on an animal shelter’s website.

In this article, we’ll summarize the main takeaways from the session that will help you maximize the time spent with an AT user and how to structure the interview to get more insights out of it.

Tips and best practices on how to structure a user interview with an assistive technology user

Build rapport. Understand the users’ typical assistive technology setup early on

“Assistive technology is like the third person in the room. If you ignore it, you’re ignoring half of what you want to research. It’s the necessary context for a researcher so the questions can be on point, and the discoveries will be useful.” — Samuel Proulx

Every user of assistive technology is unique: they may use different software, different hardware, and have different configurations. When starting a session, the first thing for a UX researcher to do is familiarize themselves with the way the participant has their assistive technology set up, and what they are using. This allows the researcher to better understand what is happening throughout the session and helps them understand the participant’s approach to technology, based on some of the access choices they made.

Stay curious. Learn how users think and operate their AT in the experience

“The key thing is if you don’t understand what’s going on, ask.” — Kavana Ramesh

As a researcher, you won’t always be familiar with how a participant’s technology works, why it works the way it does, or why they are making the decisions they make. For example, screen reader users move quickly, and often set their screen reader’s robotic text to speech voice to read out at a very high speed. It can be easy to miss things that the user is doing. Remember that participants want to provide value! They want to help you build a more accessible and inclusive world and ensure that you understand the experiences they are having. It is always okay to ask participants to pause and take time to dive into anything that is unclear. When you acknowledge what you don’t know it opens the door for you to learn even more from your participant.

Be prepared. Pivot and redirect users as they encounter overt and covert barriers

“It‘s worth acknowledging that in accessibility research especially, there are usually things that a participant may experience that I couldn’t have foreseen because I don’t use assistive technology myself. That gap already sets me up with the need to redirect if we get off the course I’ve planned.” — Kavana Ramesh

Unexpected barriers can pop up when conducting UX research with assistive technology users and can sometimes be a delicate balance. Barriers can pop up in areas that are outside the scope of your research –– perhaps you’re attempting to research a check-out flow, but you find that the add to cart flow is presenting obstacles for the participant. It is important to realize that encountering these surprising barriers is a normal part of accessibility research. Ensure you are prepared to listen, acknowledge and understand these unexpected insights with your participant before you redirect the session to what is in scope. There is value in documenting and noting out of scope findings to share with the right team or follow up on in future research.

Learn to adapt. Acknowledge and understand the user’s experience, but don’t stop there

“It’s important to differentiate between a full blocker, in that it would be technically impossible for me to proceed, maybe because my screen reader can’t press a button or I can’t find a particular element, versus the kind of blocker where in real life I wouldn’t do something. And then we (researcher and participant) can agree to move forward anyway for the sake of the research.” — Sam Proulx

Researchers must strike a balance between ensuring the participant feels supported, and finding ways to redirect, adapt, and move the research along to the priority items for the session. Offer participants the chance to share context and acknowledge a partial blocker, before continuing onward. This encourages a supportive and receptive research dynamic where both participant and researcher are aligned on the ultimate goal, which is to continue investigating accessibility. And it also produces a more holistic result from the research session: what is tangentially related to the thing that you are researching still may be having a big effect on that task.

Deciding when to encourage moving along from a sticking point should be grounded in the participant's wellness as much as in the interest of time constraints. Some assistive technology types offer many potential workarounds to try when facing a barrier, but grinding away at one component of the task can cause undue stress and can run out the clock for a session.

Utilize the opportunity. Investigate and ideate on how to make a more accessible experience together

“The biggest thing I try to do is acknowledge and understand the blocker. I’ll ask questions like `how does it impact you at this stage if you can’t proceed?’ Or `How does it impact you that something did not work, or that [X] element was not active’, and really understand the impact on the user.” — Kavana Ramesh

The best way to ensure that experiences that are not working well for an assistive technology user are resolved is not by counting code errors or crawling through technical discussions. It is understanding what the participant is experiencing now, as well as helping them imagine and explain what a better experience might be.

Conclusion

As with any UX research, the key theme is always curiosity. While conducting UX research involving assistive technology users may channel and direct the essential curiosity of any researcher into new and unexpected directions, it does not have to be a complex or difficult process. If the research is approached with the same openness and interest as any other UX research, it will be a success

Watch the full webinar to learn more from Kavana and Samuel

Watch the full example interview

The webinar features clips of the example interview that Kavana and Samuel recorded for the purposes of discussing research best practices. Check out the full recording.

Keep learning

Read more of Fable’s in-depth articles on accessibility and usability informed by both technical expertise and the lived experience of people with disabilities:

Learn more about accessibility testing and training

Questions about how you can bring insight from people with disabilities into your product design and development cycle?