The ad accessibility conundrum: community perspectives

Introduction

Advertisements are the lifeblood of business. But what happens when they aren’t accessible?

Despite people with disabilities influencing over $13 trillion in annual disposable income for themselves and their families, advertising technology hasn’t caught up to adequately capture that spending.

To better understand how accessibility impacts advertising and broader social media use, Fable surveyed our community of assistive technology users to collect their sentiments and thoughts on this topic.

This article presents some of the qualitative and quantitative data uncovered in the hopes that it will aid social media companies, advertising organizations, and the broader tech industry to better understand accessibility from the perspective of buyers.

Illustration Credit: Sherm for Disabled and Here

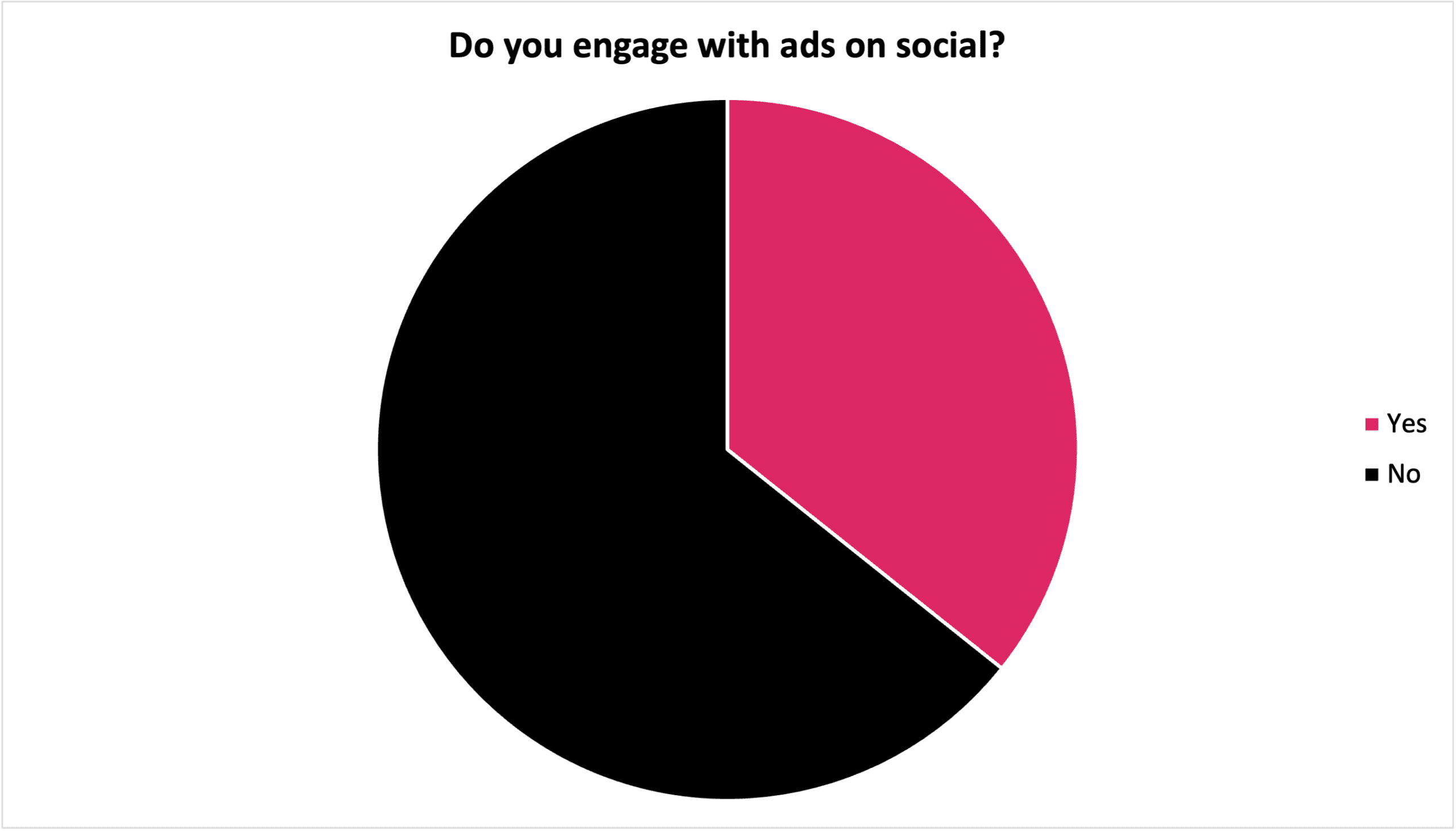

Everyone gets served ads, but not everyone can engage

The majority of people with disabilities—in line with the majority of non-disabled internet users—don’t engage with ads. By the numbers, approximately 33% of all internet users click on paid ads. In Fable’s community, 35.7% of people said they engage with online ads.

But there’s an additional factor at play: accessibility.

Of the people in Fable’s community who said they do not engage with ads, accessibility was a common reason. Many people also felt that they were served ads that felt like scams or were disruptive to their assisted user experience.

I find ads to be annoying and not very accessible. They often contain pictures which do not contain alt text. – Maryse G.

Sometimes my screen reader cannot read advertisements. But I am not online long enough and don’t post enough to get many advertisements. – Anthony H.

The advertisements can interfere with the program of accessibility sometimes which then makes it hard to navigate the website itself. – George A.

It’s worth noting that this problem cascades through different technologies, so this isn’t about blaming ad networks or individual businesses per se. While most online ads are through a small handful of networks, those networks need to follow global standards that are difficult to change. Advertisers themselves don’t control the technology behind ads and must build their marketing to fit current platform requirements. Even as networks plan for more accessibility, there are challenges with the technology available, for example iFrames or Javascript.

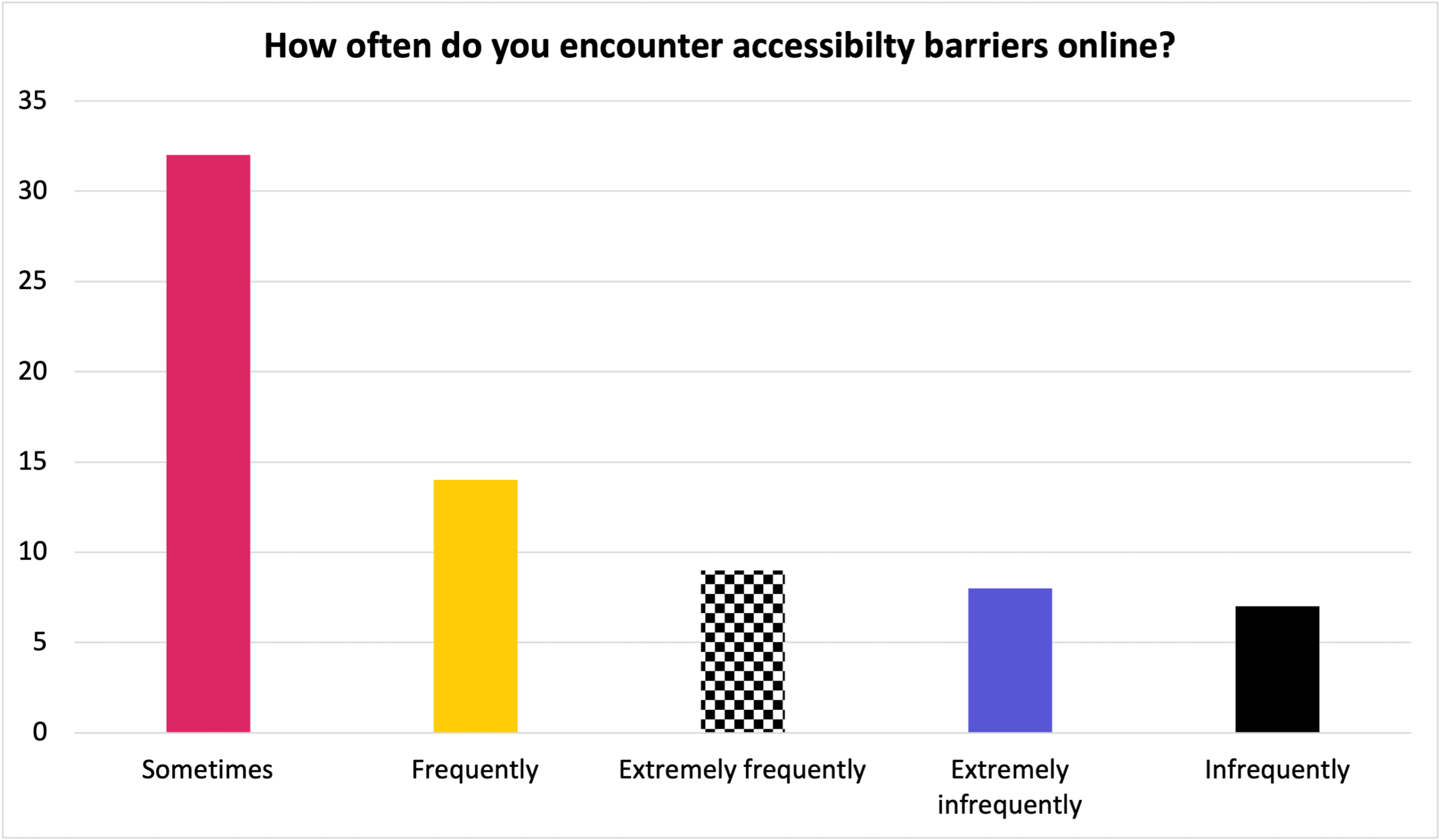

Ad inaccessibility is emblematic of social media broadly

Unfortunately, online accessibility challenges do not stop at advertisements. In a broader social media context, only 11.4% of Fable’s community did not have barriers, meaning 88.6% reported some barrier to regular or enjoyable social media use.

Sometimes my screen reader jumps all over the website. – Geza F.

It depends on the platform. If it’s Twitter or Facebook, the primary barrier is the content e.g., videos and images. For other platforms like LinkedIn, it’s more the interface. Even though accessibility has been worked on, the website still feels very clunky and not very efficient to use. – Ka L.

Scrolling is an issue where the device needs to be continuously scrolled to access more content. Encountering auto playing videos where the user is unable to use playback controls to mute or pause the video.” – Matthew D.

Most of the time, it’s images, or the way that the interface is set up. Instagram is a great example. You can set up quizzes there and they’re totally inaccessible. Most of the time, people don’t label their images there either. – Martin M.

While it’s tempting to simply not use these social media platforms, the reality is they are essential for many people with disabilities to connect with other people. There’s even an economic imperative, since many people with disabilities are shut out of traditional jobs that require full mobility or operate in small spaces where assistive devices don’t work.

Change must be intentional

Many of the concerns brought up, such as alt text, are already available on major platforms like Twitter and LinkedIn. However, Fable’s community reports they are not being used to the fullest extent.

From a forward-looking perspective, this creates a three-pronged approach to making social media more accessible: the presence of accessibility features, the intuitiveness and usability of those features, and the platform incentives in place to encourage usage.

When consuming social media, it’s the lack of knowledge by creators when it comes to accessibility. Simple things like having alt text, image descriptions, video descriptions, and being descriptive in videos instead of saying “this”. For example, there are videos where people share about this great product or book they have, but they keep pointing and gesturing at what’s on video, but I can’t read it. There’s also GIF’s which are usually incomprehensible to me. Often, I’ll respond with ‘what is that’ and I simply get a ‘what, are you blind?’ from people which is incredibly frustrating. – Carrie M.

Twitter and LinkedIn have alt text features, to continue the example, making step one (presence) complete. But the next question is whether the platform UX makes it obvious and easy to use those features, something that’s up for debate—a common example would be automatically triggering a prompt to include alt text rather than making it an optional button. Finally, it becomes a question of incentives. Since you can’t force users to do certain things on these platforms, adding alt text included, they need to be incentivized. In a social media context, an example would be changing the algorithm to prioritize surfacing content with alt text included, so creators would have a clear benefit from using accessibility features.

This same logic applies to ads. The way technology works right now, with iFrame and JavaScript insertions, isn’t accessible by default and can even hinder other accessibility features on websites. This means ad tech needs an overhaul to get to the presence of accessibility features. While there’s a problem of who takes responsibility for the first move in this space, large ad network players have the power to shift the market stance. Then the questions of UX and incentives become prominent, continuing the three-step cycle.