6 ways mobile usability fails people with disabilities

Sam Proulx

Accessibility Evangelist at Fable

There’s a perception-reality mismatch when it comes to how mobile app accessibility standards impact digital usability for people with disabilities.

I’m not saying that the various accessibility design guidelines, laws, and standards aren’t rooted in the best intentions for democratizing mobile usability. Mobile apps are increasingly considered public accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and WCAG 2.2 (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) aims to improve accessibility guidance for users with disabilities on mobile devices. The European Accessibility Act (EAA) is raising the bar by pushing for real-world usability for people with disabilities. This is all great progress.

Even with all these guardrails in place, many mobile apps still trip over the basics of accessible UX. It’s a big problem that impacts anyone whose functional approach to using apps falls outside of the “assumed average.” This includes the billions of people worldwide living with disabilities, like I do.

6 ways mobile usability fails people with disabilities

There’s a perception-reality mismatch when it comes to how mobile app accessibility standards impact digital usability for people with disabilities.

I’m not saying that the various accessibility design guidelines, laws, and standards aren’t rooted in the best intentions for democratizing mobile usability. Mobile apps are increasingly considered public accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and WCAG 2.2 (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) aims to improve accessibility guidance for users with disabilities on mobile devices. The European Accessibility Act (EAA) is raising the bar by pushing for real-world usability for people with disabilities. This is all great progress.

Even with all these guardrails in place, many mobile apps still trip over the basics of accessible UX. It’s a big problem that impacts anyone whose functional approach to using apps falls outside of the “assumed average.” This includes the billions of people worldwide living with disabilities, like I do.

Sam Proulx

Accessibility Evangelist at Fable

Mobile apps are critical for people with disabilities

As a totally blind person, I would be lost without my phone—it’s on my person or in my hand at all times. This is common behavior for people with disabilities. Among Fable’s community of assistive technology users, 41% use mobile devices for more than 4 hours a day.

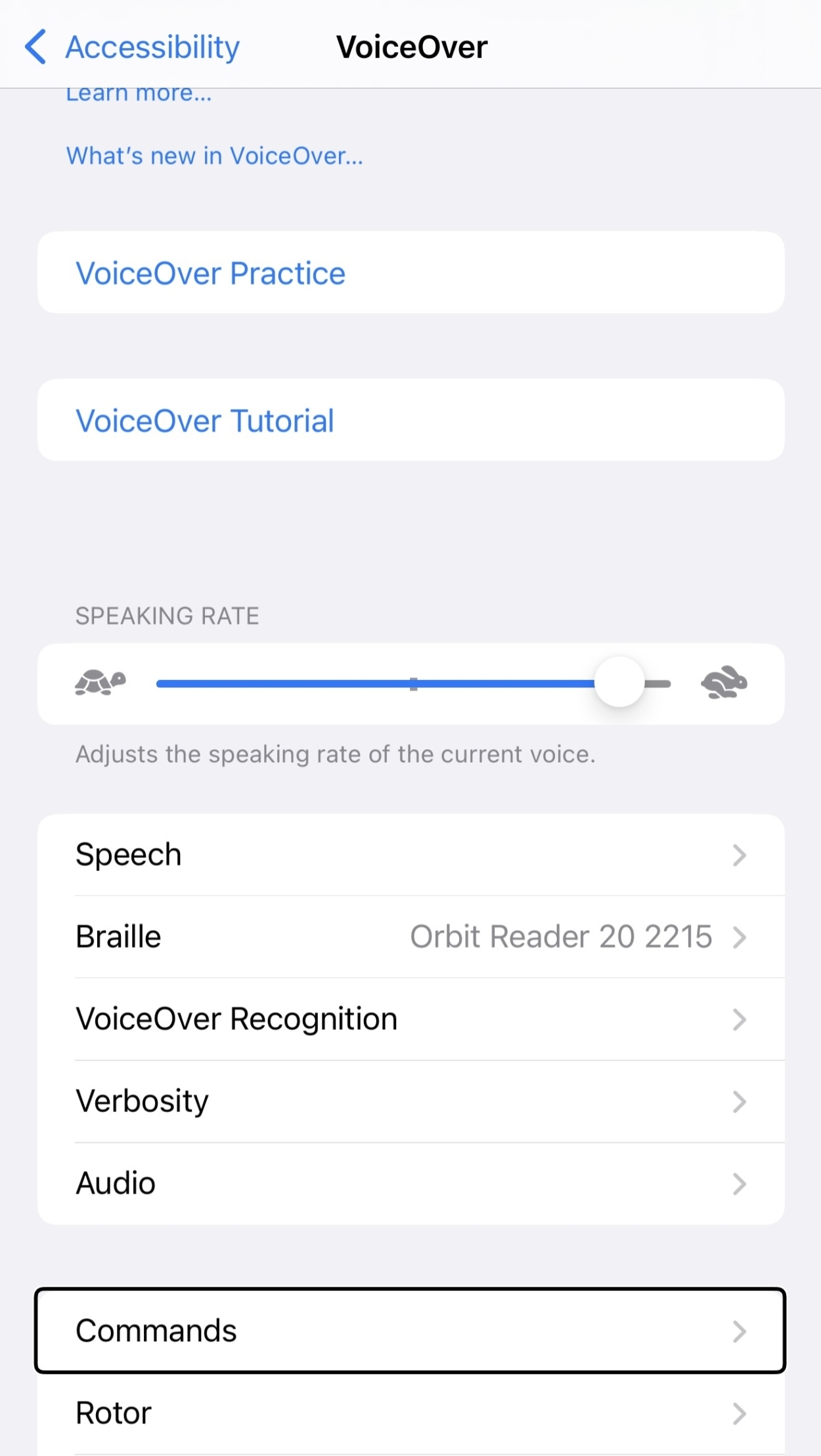

Personally, I choose to use my smartphone for most activities. I navigate mobile apps using the built-in VoiceOver screen reader for iOS. While a tablet isn’t a useful device for me, many people with different disabilities use this form factor because phone screens are too small to navigate.

It’s tempting to think that a traditional standards-based approach to accessible mobile UX design makes it easy for a wide range of users to complete desired activities—like buying groceries, ordering food, shopping for clothes, and more. But people with disabilities will tell you a very different story about their mobile user experiences.

In this article

I’m sharing 6 realities about the mobile user experiences of people with disabilities. Here’s what’s I’ll cover, in case you want to jump to a particular area:

Developers check compliance boxes. Users still hit walls.

Many mobile apps present a whole lot of unnecessary friction that forces people with disabilities to devise workarounds or go searching for a different app with fewer barriers. This isn’t just my opinion: there’s data to back it up.

The State of Mobile App Accessibility report provides a detailed analysis of the digital accessibility of apps across five different industries: payments, shopping, food and delivery, fitness and streaming. The report highlights significant digital barriers in mobile apps:

I’m not going to regurgitate a lot of specific findings here. The report does a great job of summarizing them and it’s free to download. Instead, I’d like to share a few truths that bubbled up for me as I reviewed the findings.

Reality #1: Many people with disabilities are reluctant “masters” of tech

I wasn’t at all surprised by many of the report’s findings because digital barriers in mobile apps are an everyday experience for me and so many others. Here’s just a small sample of what we frequently encounter in mobile UX design:

I feel lucky that I’m skilled at using technology. This predisposition makes it easier for me to work through many mobile usability issues. But not every person with a disability has this same experience.

Forced digital literacy is common… and problematic

Many people with disabilities develop enough skills to survive in a digital world. They slog through and figure things out so they can participate in activities like ordering an Uber, buying food, and streaming entertainment. It’s mandatory behavior as more of life moves online.

This digital literacy requirement can be problematic for some. For example, people who are aging into disabilities—a common phenomenon in countries with life expectancies over 70 years. Data suggests that individuals in this demographic will spend, on average, 8 years living with disabilities.

These acquired disabilities can take many different forms—both visible and invisible:

Today’s 65+ crowd were born well before home computers, the internet, or smartphones. Any adoption of mobile apps occurs later in life.

This is not to say that there aren’t also competent tech users in this demographic. But, regardless of tech literacy, learning how to navigate new platforms and interfaces is, well, hard. This leads me to another moment of truth.

Reality #2: Muscle memory keeps people with disabilities tied to certain apps

The data does a really good job of explaining why I, like many people with disabilities, consistently use the globally popular apps over more niche apps (think: Amazon vs a bunch of individual store apps). It has everything to do with muscle memory.

The report revealed an accessibility score of Fair across apps and industries. That score happened thanks to a whole lot of mobile usability issues in play. When people with disabilities learn to work around the accessibility problems in one app, we tend to stick with what we know. Learning a new app often means navigating a whole new set of digital barriers. It’s way easier to remember the workaround for an accessibility issue already encountered.

Long-term OS brand loyalty is also the norm

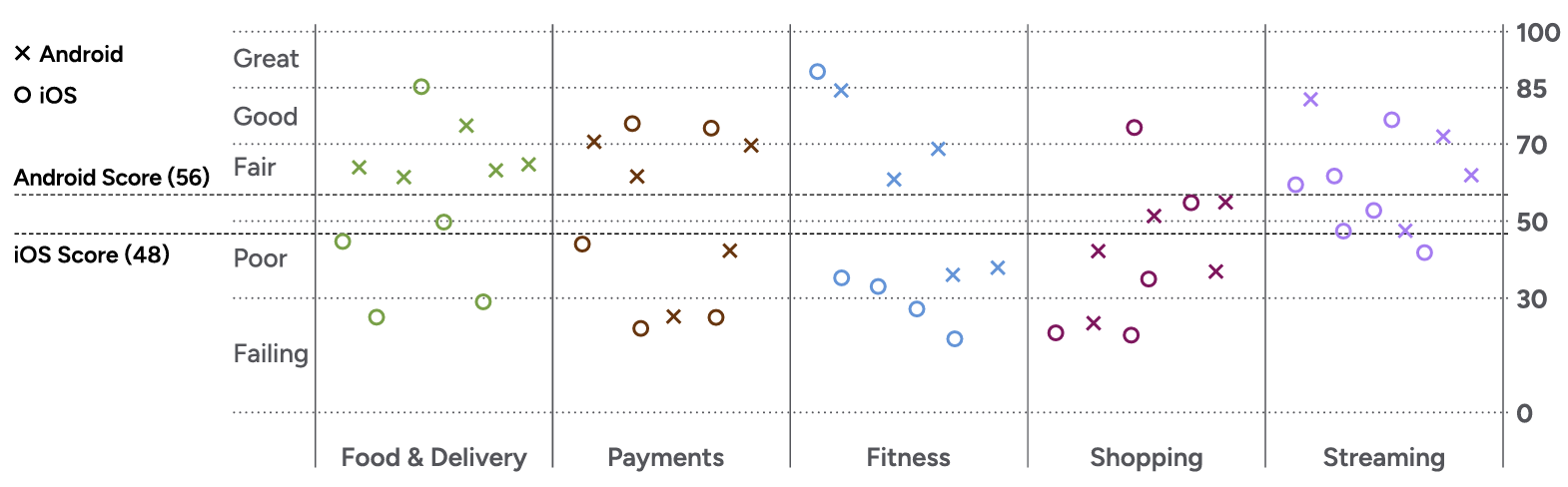

The report gave iOS apps a slightly lower App Accessibility Score than Android (48 for iOS vs. 56 for Android). It’s a small difference and certainly doesn’t negate the fact there are a lot of great-performing iOS apps.

App accessibility scores for Android vs. iOS

Source: State of Mobile App Accessibility Report by ArcTouch

A finding like this doesn’t indicate an imminent mass exodus off the iOS platform by people with disabilities. A lot of us originally chose iOS because it was the best at accessibility for so long. Switching now to an unfamiliar operating system is problematic for a couple of reasons:

- No “try before you buy”. There’s no way to evaluate whether Android’s approach to accessibility meets my needs until I’ve already purchased a phone. I’m not going to buy a phone based on the hope that I’ll like the accessibility options.

- Familiarity breeds comfort. Changing tools requires a lot of thought, effort, and re-learning. As I said earlier, “muscle memory” is a big factor in people’s comfort with and loyalty to certain apps. The same principle applies to operating systems.

Reality #3: Home page scrolling is a luxury we often don’t have

I’m not surprised that 46% of home screens received Poor of Failing grades from the report. I’ve encountered a lot of issues across app home screens. This means that when I open an app, I know exactly what I want to do.

Discovery browsing isn’t an easy, fluid process for me. Instead of scrolling through the home screen, I go right to search because I know that’s the best way to find what I’m looking for. This is another reason I use the more central apps: they always have search functionality.

Reality #4: There’s an accessibility/security tradeoff for people with disabilities

Using features that make mobile apps more accessible often means compromising on security and privacy. I personally don’t turn off any privacy settings because I find they negatively affect the mobile user experience. Here are two examples for further context:

If I want to take an Uber, I can’t disable my location access on my phone

This is because the workaround when that setting is turned off is for the user to type in a desired pickup address, which is difficult. Alternatively, you can drag the pin on the map to the exact desired pickup spot. As a totally blind person, I quite literally can’t do that. I must give up some privacy and allow location tracking.

If I disable website cookies, I can’t stay logged into a payment app like PayPal

Payment is so much simpler using the express checkout option on an app because it automatically populates everything required for smooth check out. Disabling cookies blocks behind-the-scenes data exchange, meaning the express checkout button may not appear at all, autofill won’t work, or the user gets logged out of PayPal mid-transaction.

Choosing more privacy means manually entering payment, shipping, and billing details and dealing with other accessibility barriers that are different across checkout experiences. Many users will trade off privacy to eliminate the frustration.

Reality #5: Embracing customization can further stigmatize people with disabilities

When it comes to mobile UX design it’s tempting to believe that allowing more user customization can better support accessibility. This makes sense on the surface, but it has the potential to make things harder for people with disabilities.

If users have the option to change everything, they don’t like it can lead to sub-optimal defaults. (Because they can be changed, right?) The trouble is, customizing defaults to align with preferences isn’t straightforward for every user.

This approach not only cuts people off from digital experiences, but it can also be stigmatizing. When there are “accessible” alternatives available, those without lived disability experience might scratch their heads wondering why someone isn’t taking full advantage. They don’t understand that accessible doesn’t always equal usable.

Reality #6: Doing things offline is increasingly not an option

At the beginning of this article, I said I prefer to use my smartphone for most activities. That preference is quickly turning into an imperative as it gets slightly harder to live offline every year. Let’s explore this through the experience of banking.

Banking through an app on your phone makes a lot of sense. But if that app is lacking accessibility basics—like properly labeled buttons, image descriptions, and support for landscape orientation—then a frustrated user might be tempted to go into a physical branch instead. Not so fast.

With branch closings, you might have to travel further to get to one that can serve you. You might also be dealing with more limited hours of operation and even a charge to meet with a banking rep. Getting to a physical branch can include even more barriers. If you’re ordering a cab or Uber, you also need to do it through an app. And if you live in a small town without public transit options, well, you’re right back online.

Repeat this scenario from everything from buying clothes to getting groceries to doing your taxes. Friction and access barriers are everywhere.

The ripple effect of mobile usability issues

Living in this increasingly digital world means millions of people are using inaccessible apps and figuring out workarounds. Sometimes giving up is not a choice. They have to do the thing, so they do it. But if they hate the experience, they won’t just quietly endure it.

It’s time to widen the definition of accessibility (here’s how)

Accessibility is about functionality. It’s about the ways different people interact with technology, information, and the world around them. There’s a whole lot of nuances to keep in mind.

Making mobile usability a reality for every user requires an inclusive design approach. It’s about moving beyond the “average user” mentality of the past, stretching beyond compliance, and embedding meaningful accessibility into mobile UX design from the start. The payoff comes in building long-term trust and brand loyalty with a massive group of humans desperately seeking digital solutions that help them exist in the increasingly online world.

Help for exploring inclusive design

A great place to start with inclusive design is connecting with a community of people who can help you understand their lived experiences when it comes to navigating mobile apps. Whether you need insights from particular assistive technology users or require access to people who require cognitive accommodations, Fable can help you gain the insights to design experiences that actually work for everyone.